This weekend culminates rivalry week in college football, and that means “The Game” between Ohio State and Michigan. The Game conjures up memories of the Toledo War and the Frostbitten Convention. And it occurs on a weekend with games that have awesome names like “The Iron Bowl” (Alabama-Auburn), “The Civil War” (Oregon-Oregon State), “The Egg Bowl” (Mississippi St.-Ole Miss) and “The Holy War” (BYU-Utah).

But only one of these rivalry games can claim an actual war to have once transpired in the local history of that specific geographic region. That’s the Michigan Wolverines vs. the Ohio State Buckeyes, or “The Game,” as it’s called.

Well, maybe two rivalries can claim actual battles: Kansas-Mizzou, given the abolitionist vs. slave state skirmishes known as “Bleeding Kansas,” in the 1850s. You just don’t get this with NFL football. Not quite at this level of acrimony. Although, as Super Bowl winning tight end Vernon Davis articulated to RG, the NFC East division does have some pretty intense rivalries, between/among multiple teams, within it.

Because I’m a history dork (you may have seen me compete, ok not compete, DOMINATE, on “How The States Got Their Shapes” on the History Channel, the “Great Lakes, Big Stakes” season two, episode 8) who loves things with names like “The War of Jenkins Ear,” “The Era of Good Feelings” and “Merkle’s Boner.

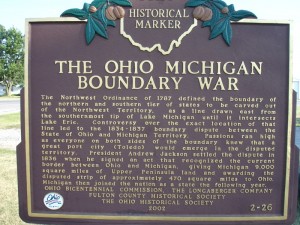

So let me tell you about the boundary Toledo War, well, it was kind of a war, more of a skirmish, over the Toledo Strip between Michigan and Ohio, and of the “Frostbitten Convention” that ended it.

Varying interpretations of laws passed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries caused the governments of the state of Ohio and the territory of Michigan to both claim sovereignty over a 468 square mile region along the border known as the Toledo Strip. Yes, believe it or not it was Toledo that was deemed valuable enough to fight for.

When Michigan sought statehood in the early 1830s, it’s pitch included the disputed zone it considered within its boundaries. Ohio’s Congressional delegation responded by halting Michigan’s admission to the Union.

Beginning in 1835 both sides passed legislation attempting to force the other side’s acquiescence. Relations between the two governments went from just frosty to openly hostile.

On July 15, 1835, tensions finally overflowed and blood was spilled. Sort of.

Monroe County, Michigan Deputy Sheriff Joseph Wood went into Toledo to arrest Major Benjamin Stickney, but when Stickney and his three sons resisted, the whole family was taken into custody.

During the scuffle, Two Stickney, son of the major (yes, that actually was his name and the other son was named One Stickney), stabbed Wood with a pen knife and fled south into Ohio.

Wood’s injuries were not life-threatening. When Ohio Governor Robert Lucas refused Mason’s demand to extradite Two Stickney back to Michigan for trial, Mason wrote to President Jackson for help, suggesting that the matter be referred to the United States Supreme Court.

At the time of the conflict, however, the Supreme Court could only resolve state boundary disputes, and Jackson declined the offer. Looking for peace, Lucas made his own efforts to end the conflict, again through federal intervention via Ohio’s congressional delegation.

In December 1836 the Michigan government, facing a dire financial crisis, surrendered the land under pressure from President Andrew Jackson and accepted a proposed resolution adopted by Congress.

Michigan had to forfeit its claim to the strip in exchange for statehood and approximately three-quarters of the Upper Peninsula.

The Toledo War, if you could call it that, included some militias staring down each other and shouting at one another, but they only fired up into the air above, and not at each other.

The Battle of Phillips Corner was not an actual battle.

The Toledo War ended on December 14, 1836, at a second convention in Ann Arbor.

Yes the very same place that is home to UM. However, the calling of the convention was controversial. It only came about because of a public outcry. Since the legislature did not approve a call to convene, some said the congress was illegal.

Congress questioned the legality of the convention before finally accepting its solution. Because of it’s questionable nature, as well as the historical cold wave at the time, the event later became known as the “Frostbitten Convention.”

Today, conflict between the two states is limited to the Michigan–Ohio State football rivalry. This does not involve militias, muskets and pen knife wounds like you had in the Toledo War.

The Toledo area is about half and half in its allegiance, and considered the DMZ between maize and blue vs. scarlet and grey. The city has large contingents of partisans for both schools, but it’s much closer to Ann Arbor than Columbus geographically.

However, it’s located in the same state as THE Ohio State University.

Paul M. Banks is the Founding Editor of The Sports Bank. He’s also the author of “Transatlantic Passage: How the English Premier League Redefined Soccer in America,” and “No, I Can’t Get You Free Tickets: Lessons Learned From a Life in the Sports Media Industry.”

He currently contributes to USA Today’s NFL Wires Network, the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America and RG. His past bylines include the New York Daily News, Sports Illustrated and the Chicago Tribune. His work has been featured in numerous outlets, including the Wall Street Journal, Forbes, the Washington Post and ESPN. You can follow him on Linked In and Twitter.