By Jeremy Harris

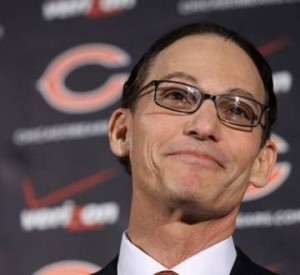

Bears’ head coach Marc Trestman should take heed.

On October 12, 1997, the Chicago Bears trailed the Green Bay Packers 24-17 with just under two minutes left in regulation when they cut the deficit to 24-23 on a touchdown pass. Head coach Dave Wannstedt called for a two-point conversion that the Bears failed to convert, effectively ending the game.

After the game, Wannstedt explained that he opted for the two-point conversion because he did not want to give Packers’ quarterback Brett Favre a chance to lead his team to a winning field goal in regulation. This explanation defied basic logic because, whether the Bears had kicked the extra point and tied the game or taken a one-point lead by converting the two-point conversion, Favre still would have had the same opportunity to drive his team for the winning field goal in regulation.

Blunderous decisions and incoherent justifications came to define Wandstedt’s disastrous six-year tenure with the Bears (1993-1998), which ended with a fan mutiny and players making little effort to disguise their contempt for the head coach.

Fast forward sixteen years. When the Bears hired Trestman, cogent decision making seemed to be a foregone conclusion from the highly articulate coach with a law degree in addition to twenty years of NFL coaching experience. Yet Trestman is proving appallingly inept at handling this critical job responsibility. Moreover, his blathering postgame justifications would make a mother proud of her son’s explanation for how the cookie jar attacked his hand.

We previously wrote about a series of disastrous decisions made by Trestman when the Bears hosted the Detroit Lions on November 10, 2013 that literally rescued defeat from the jaws of victory. Last Sunday against the Minnesota Vikings and two weeks earlier against the Baltimore Ravens, Trestman might have exceeded his previous incompetence.

Against the Vikings, Trestman opted to kick a 47-yard field goal on second down with 4:12 remaining in overtime after running back Matt Forte had gained three yards rushing on first down. Gould’s kick sailed wide right after which the Vikings drove the ball deep into Bears’ territory for the winning field goal, dropping the Bears’ to 6-6 and seriously jeopardizing their playoff chances.

Trestman defended his decision by noting that the Bears were within Gould’s range, that he was concerned about losing yardage on a penalty or an offensive play, and that there was no guarantee that the Bears would have gained yardage on subsequent downs.

Clearly the Bears were within Gould’s range from 50 yards when Trestman opted to run Forte on first down, so why did these same concerns not compel Marc Trestman to kick the field goal then?

The Bears had committed only one holding or false start penalty on Sunday and were averaging 5.4 yards per run against the Vikings. Trestman’s lack of confidence in the Bears’ offense on second down was both alarming and insulting considering that it had churned out 480 yards. Forte has fumbled just two times in 272 touches this season, a .007% rate. This data should have dismissed Trestman’s concerns about a penalty, lost yardage, a turnover or his offense’s continued proficiency.

Further statistics also undercut Trestman’s decision. Prior to Sunday’s miss, Gould had converted on 73% of field goals between 40-49 yards. Yet his accuracy rate between 30-39 was 90%. More generally, since 2000, NFL kickers have converted 47-yard field goals at a 75% rate. Their accuracy rate improves to 80% when they kick from just four yards closer. The percentage of aborted holds on field goals since 2000 is less than 1/2 of 1%.

Thus Trestman had at least one play and, if he were playing the percentages to which he claims to be such a proponent, likely two plays to substantially increase the odds of Gould converting the winning kick. And had the Bears gained a first down, they could have continued to try to gain yardage and increase Gould’s odds while also draining the clock to prevent the Vikings from mounting a drive of their own in the unlikely event of a Bears’ turnover or Gould missing an even shorter kick.

Finally, there is the human factor that mitigates even further against Trestman’s decision. Gould arrived on a separate flight from the team to Minnesota after being with his wife when she gave birth to the couple’s first child. He was playing on zero sleep and was emotionally drained. After the Bears had called a timeout to set up a field goal, Minnesota responded by calling one in succession prior to Gould’s kick. Gould had run from the sidelines to the line of scrimmage back to the sidelines and back to the line of scrimmage, probably 200 yards, before attempting the ill-fated kick. Another offensive play or two would have helped Gould regain his wind.

There is simply no defense for Trestman’s reckless decision, which denied his team an opportunity to substantially increase the likelihood for a successful outcome.

Two weeks earlier, Trestman nearly gift-wrapped a victory for the Baltimore Ravens with his mind-boggling end-of-regulation clock management and then offered a dizzyingly illogical postgame explanation.

With the Bears leading the Ravens 20-17 late in the fourth quarter in a game they would eventually win 23-20 in overtime, the Ravens mounted a late drive. With 1:16 second remaining, the Ravens reached the Bears’ five-yard line with the clock running and the Bears possessing all three of their timeouts.

The Ravens allowed the clock to run down to :36 before running back Ray Rice gained three yards to reach the Chicago two. Baltimore called its second timeout with :23 remaining. After Rice was stopped for a one-yard loss, Baltimore used its second timeout at the 11-second mark. Ravens quarterback Joe Flacco threw incomplete on third down, and the Ravens kicked the tying field goal with just seven seconds left in regulation.

After the game, Trestman was asked why he did not use the Bears’ first timeout at the 1:16 mark when the Ravens had reached the Bears’ five as a contingency in the event that Baltimore scored a touchdown and Chicago needed time to drive for a touchdown of its own down 24-20.

Trestman justified the decision, in part, by noting that teams starting from their own 16-yard line, which Baltimore did, have just a 13% probability of scoring a touchdown. For someone who is married to the rules of probability, it is shocking that Trestman could overlook its most elementary rule: the percentages reset when the circumstances change. The average red zone touchdown conversion rate is approximately 54%, not 13%, regardless of where a team’s drive starts.

Trestman also stated that had the Bears taken their three timeouts in succession starting at the 1:16 mark, they would have been left with only eighteen seconds. However, Trestman reached that figure based on an assumption that the Ravens would run the ball on three consecutive plays (which they did not) and would not score a touchdown. Both were brazen assumptions.

If the Ravens had scored a touchdown on second or third down, the Bears would have been left with 20 to 30 seconds to score a touchdown of their own. Conversely, had the Bears called a timeout at the 1:16 mark and the Ravens scored on the next play, the Bears would have had over a minute and two timeouts to try to traverse the field for a winning touchdown, a far better set of circumstances for the offense.

Trestman’s final explanation for not calling timeouts was that he did not want give the Ravens the opportunity to substitute red zone, for their two-minute, personnel. This explanation is utterly preposterous, as the Ravens had two timeouts andfull play clocks to make these substitutions.

That Trestman did not consider the option of preserving time to play for a win in regulation had his defense held the Ravens to a field goal, especially considering the game breaking abilities of kick returner Devin Hester, is difficult to comprehend. That he put the Bears in a position where a Ravens’ touchdown would have effectively ended the game and the Bears’ three timeouts would have served as nothing more than parting gifts was as inexcusable as his justifications were illogical, inaccurate and assumptive.

Though we suspect that Trestman’s decisions cost the Bears games against Minnesota and Detroit, there is no way to be absolutely certain. What is certain is that he is consistently foundering at his responsibility to put his charges in the best position to succeed. There are no training wheels for decisions like those Trestman has butchered. A surgeon is expected to know he has to wear gloves when examining a patient his first day on the job.

Players risking their livelihoods on a weekly basis are anything but robots. They expect better, as will prospective free agents. A restive fan base is already experiencing buyer’s remorse. Trestman’s moves have not been cerebral, pioneering or cutting edge; they have been asinine. And there is no gray area to debate their merit.

Trestman deserves tremendous credit for his exemplary work upgrading the offense and should be completely absolved of the poor play of a defense besieged by several injuries to significant players. Yet if he does not improve his game management decisions, his head coaching tenure in Chicago promises to be brief and inglorious.